ADOBE BUILDING, RITUAL AND HEALING

Written by Sarah Sao Mai Habib

Hardcover, 108 pages

25 copies made, ready to print at scale · Shown at “Brick x Brick: Artworks Inspired by Earthen Architecture” exhibit in Santa Fe, New Mexico

Complete Text Below

ساره ساو ماي حبيب · Sarah Sao Mai Habib

{Online Version} Mushroom Books 2023

ISBN 978-0-9961744-5-9

ABSTRACT

This work centers on the idea of home sovereignty, which refers to community self determination related to home & belonging. This work is contextualized within integrated liberation efforts of land, food/medicine, housing, spiritual & cultural sovereignty, intersectional healing, and kinship beyond borders. This is done through the framework of adobe – a building material made of earth and other natural elements.

It is an offering consisting of eight parts that weave in and out of the specificities of current & historic adobe use in New Mexico/Pueblo Land and globally. Each part builds off one another, and can exist on their own. The sections include: 1. Acknowledgements & introduction to myself, research themes, objectives & approach. 2. Place based experiences that have informed this work (Dinétah & Bluff, Syuxtun, and Pueblo Land). 3. Rina Swentzell introduction to ground us in a lineage of matriarchal ancestral wisdom. 4. The scales of relational infrastructure & maintenance embodied in adobe building and beyond. 5. The challenges to relational maintenance in adobe & beyond. 6. Repairing & reinvigorating cultures of belonging through earthen building and beyond. 7. Questions I leave you with. 8. References and resources.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This project was started & completed in O’gah Po’geh, the Tewa village name for what is now known as Santa Fe, New Mexico. I am thankful for, and owe the possibility of this project to the powerful relationships between land & people here in Pueblo Land, and all the ways I was supported & welcomed into this work.

Contents

Introduction

Kuwait

A Note on Research

1. Place

Dinétah & Bluff, Utah

Syuxtun, Chumash Land (Santa Barbara, California)

Pueblo Land (Northern New Mexico)

2. Matriarch

Rina Swentzell

3. Relationship

Scales & Circles of Relational Infrastructure

What Disrupts The Maintenance of Relational Infrastructure

Repairing & Reinvigorating Cultures of Belonging

4. Questions

Appendix

References

Images

Non Comprehensive Resource List

Practices, People, Buildings

Books, Podcasts, Videos, Lectures, Reports & Articles

Exhibits

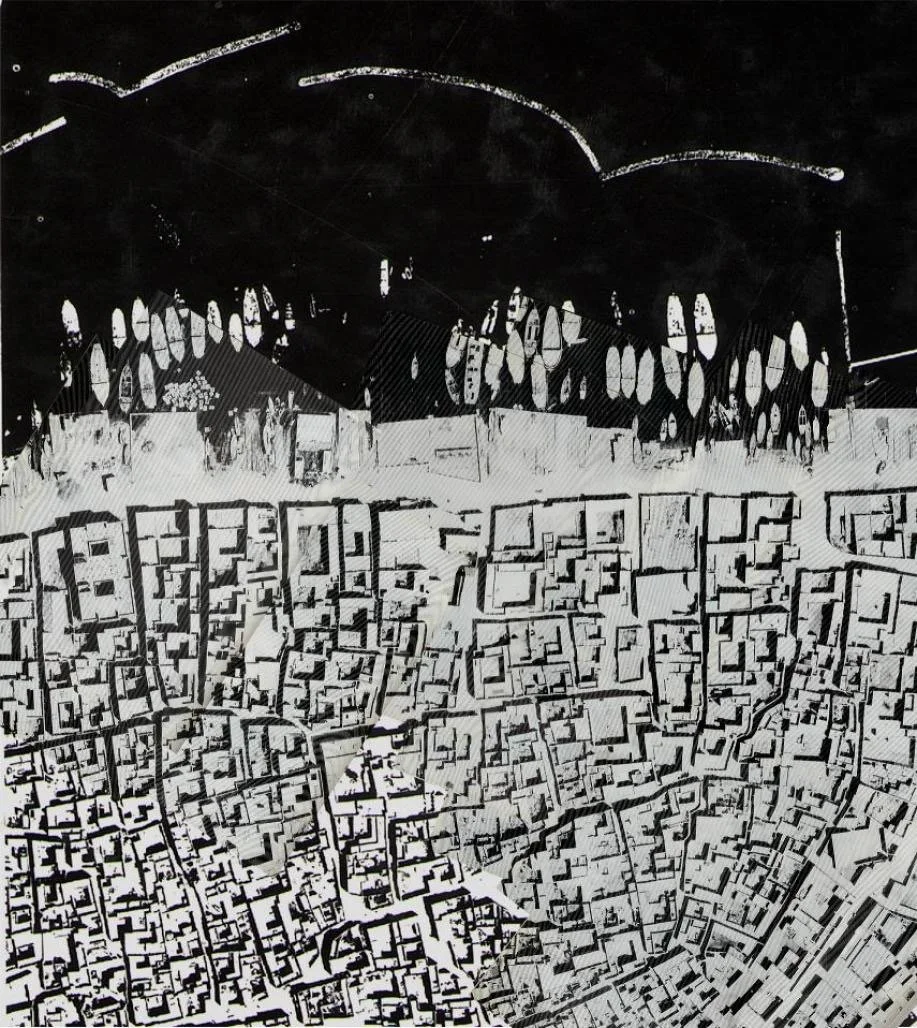

Aerial of early twentieth century Kuwait. Adobe & stone courtyard homes along narrow alleys, near the Gulf & maritime activities. (fig. 1)

KUWAIT كويت

We are made of clay. I grew up hearing this origin story: that the divine shaped us from clay and breathed life into us Al-Nafs النفس . I was born in the desert and near the ocean, cradled by countries now known as Kuwait, Iraq & Iran.

There was a natural spirituality that imbued all aspects of personal & community life that I never thought of as separate from living or engaging all my senses with. It was evident in the architecture. Minarets peaked above perpetually dusty buildings, singing us into prayerful reminders of the five daily cycles of sun. Sheep were offered to new homes and communities on feast days Eid عيد after long journeys & fasts.

I remember the physical vessels of home shifting from a mid rise apartment to a house my parents were involved in designing but not building. In Kuwait, most residential buildings are now made of concrete, unlike the older stone & adobe structures scattered throughout preserved historic sites. The discovery of oil catalyzed tremendous change in Kuwait. Family members who have witnessed this transformation tell me of dirt roads where there are now highways, highrises and opulent consumer centers. I always felt the tense swirl of old/new/local/foreign values that existed on this land, which was a British “protectorate” up until the 1960s.

Traditional buildings of adobe & coral stone homes had central courtyards, and were clustered near The Gulf. Kuwait’s livelihood & culture relied directly on water, as well as nomadic desert pastoral ways prior to the fossil fuel, European & US imperialist eras. I remember seeing photos of the Gulf war, most notably the ominous black clouds from oil fields set ablaze, and mud brick homes riddled with bullets. For me, those photos collapsed multiple timelines: buried pasts, extraction, native lifeways, nomadic dreams, and colonization.

No one is outside the effects of dispossession, displacement, or colonization. However, some of us have memories that are a shorter walk to. Those of us with memories of being severed from our lifeways & homes, so alive & so close, hold the healing wisdom to circle back to what we once knew as our birthright1. This piece expands on the ideas of home sovereignty (in context of other sovereignty work, intersectional healing, and kinship beyond borders) through the framework of adobe - a building material made of earth and other natural elements.

A NOTE ON RESEARCH

My intention for this introduction is to share a bit of who I am, my experiences, and how the themes of home, adobe, earthen building, belonging, and relational infrastructure cycle throughout my life in new, old and purposeful ways. I hope giving you some context of how my lens is shaped may prompt you to reflect on your lens. We all move within contexts that defy “objectivity”, yet center us in our unique purpose.

In general, I intend for this work to be a pathway to starting new and strengthening existing relationships with ideas, beings, places, projects and people (especially related to the themes explored). I hope this can serve as a springboard for ongoing learning and collaboration. The harm & violence that happens when differences are not respected should not be bypassed. Moving a step beyond that: the more we learn, uplift and support each other in our different ways, the more we will be able to thrive in our collective ecology of ways.

This written form is a time capsule of where my learning exists, at this moment. I hope to return to this archive as an aid for self reflection, accountable change and growth. Alongside these lofty goals, coexist the inevitable shortcomings of conveying what I learn from direct experience and oral tradition in written English format. Although I do not have simple answers to resolving the tension between these methods, I do want to acknowledge them and acknowledge the historic and contemporary alchemy that oppressed people of color create through these very challenges. My prayer is that I continue this lineage of restorative alchemy.

Having experienced Euro-Western academia, I also know the violence these institutions perpetuate, which look like erasure & devaluing diasporic, indigenous, mystic and intuitive knowledge. Like many students of culture, My core sense of self and innate wisdom was often doubted. Because of this and its implications on the maintenance of cultures that sustain humanity, I am deeply committed to naming & unlearning all the colonial and oppressive ways that were instilled in me. I actively engage with the work of those on similar journeys such as Shawn Wilson who wrote the book “Research Is Ceremony” , which has inspired me and given me more language for research methods rooted in relational knowledge building & healing2. As a result, this work will not resemble a typical research report, and will attempt to directly challenge what it means to center knowledge that is based in formal Euro-Western academic scholarship or formal “professionalism”. Embedded in all sections of this offering, are stories, references to different knowledge keepers, and a reverence for working directly with material and practice.

When I immersed myself in the world of adobe here in New Mexico/Pueblo Land, it quickly became clear that the most relevant knowledge lives within people, places and practices, and is not necessarily well recorded or documented. In many ways the adobe buildings that still stand today are embodied archives of the required relationship and reciprocity, which the buildings are simultaneously a result of and conduit for.

Again, this work is about home sovereignty, and the relational & multi-dimensional healing embodied within adobe building & maintenance. This offering consists of several parts that weave in and out of the specificities of adobe and other research themes. They will build off of one another, and can also exist on their own. So there may be repetition that speak to the spiral nature of this knowledge seeking:

Place based experiences that have informed this work (Dinétah & Bluff, Syuxtun, and Pueblo Land).

Rina Swentzell introduction to ground us in a lineage of matriarchal ancestral wisdom.

The scales of relational infrastructure & maintenance embodied in adobe building and beyond.

The challenges to relational maintenance in adobe & beyond.

Repairing & reinvigorating cultures of belonging through earthen building and beyond.

Questions I leave you with.

References and resources.

DINÉTAH & BLUFF, UTAH

I was researching online and to my delight, I came across a thesis titled “Building Reciprocity: A Grounded Theory of Participation in Native American Housing and the Perpetuation of Earthen Architectural Traditions” by Tonia Sing Chi3. I decided to contact her, and we had a lovely conversation. Thanks to Tonia, I was invited to the Nááts’íilid Initiative meeting in the four corners area (where the state corners of New Mexico, Utah, Colorado and Arizona meet). Nááts’íilid Initiative describes one of its missions as strengthening “the cultural and economic resilience of Dinétah through self-reliance initiatives in the built environment” 4. This would be the initiative’s (as well as my) first in person meeting of this sort since the pandemic began a year and half ago. Needless to say I was excited, and a little nervous. But I trusted the process and made the 5 hour drive from Santa Fe.

It was two full days that started and ended in prayer, two days of sharing intentions, dreams, challenges, and discussions of home: from the immaterial to the physical, planning, building, caring of home, and to the disruptive policies layered in bureaucracy. It was a true honor to be invited into a community, to learn about housing, home and life in the Navajo Nation, and especially to hear stories from elders.

As a guest, I was invited to share some of my experiences and it jogged back memories of my younger life in Kuwait. I could feel the connections being made between our cultures. I was reminded how the way we relate to land shapes our cultures, our homes and how we build. I was reminded how across borders we honor transitions in life with reverence, remembrance and ritual. And how jokes, laughter and good food close the distance between us. I left recommitted to our collective responsibilities to build and unbuild in ways that heal, and move us towards more equitable relations, true wealth and safety.

SYUXTUN, CHUMASH LAND (SANTA BARBARA, CALIFORNIA)

Santa Barbara is known to be a wealthy vacation & retirement town with all the typical amenities packaged in a romanticized Colonial architectural aesthetic. I moved to the central coast of California after being hired for a construction & community outreach job with Habitat for Humanity in Southern Santa Barbara. Because I was working for an affordable housing organization, I got to experience a completely different side of town than its stereotype. But like other rich places, you will also find the social infrastructure that makes affluence possible: poor and working class farmers, educators, delivery, maintenance, service & retail industry workers. During my initial months, I was working almost exclusively with the trailer park communities, renovating and weatherizing mobile structures, which was very different from the stuccoed world of downtown & surrounding areas.

The city of Santa Barbara as we now know it, was built around the Presidio and Spanish Mission. The Mission & its Spanish Colonial Revival style buildings, situated between mountain & ocean, have proven successful in attracting people to continue living and shaping this community. Through the use of material and process like: adobe, mosaic, strict zoning, density & height limits, the building entities in Santa Barbara pride themselves in maintaining its cultural heritage. However, the underlying assumptions of this version of heritage preservation, and how it intersects with issues of equity, massive environmental, economic, political, demographic, and mobility issues are rarely questioned.

In California, iconic adobe architecture was spread along the coast through Spanish missionizing. What is left out in the public narratives of these buildings is the fact that they were built by indigenous slave labor, and are sites of marked and largely unmarked graveyards 5 6.

The historic erasure, colonial romanticization, aestheticization and resultant gentrification of Santa Barbara, had created a demand to mimic adobe construction often through a veneer of stucco on stick framed buildings 7 8. These gestures of building and accompanying narratives, attempt to manufacture a sort of “authenticity”, and preserve a glorified colonial history. Beyond notions of beauty and aesthetics, architectural preservation remains highly political. Colonially centered preservation efforts are akin to maintaining hollow shells, when cracked reveal a void where truth, accountability and reparations are missing. Tizziana Baldenebro’s essay “The Trial of California’s Missions” offers us some suggestions to answering the question: “how do we hold buildings accountable?” . Baldenebro suggests publicly including (and integrating in the design and architecture) indigenous & other historically silenced narratives. In addition to transforming these spaces into community centers with & for the most harmed where cultivating healing, nourishment & joy is made possible9.

PUEBLO LAND (NORTHERN NEW MEXICO)

When I first lived in New Mexico, I thought I was done with architecture, but little did I know then, it would be the beginning of a circuitous route back to it, this time in a way that felt deeply aligned with my purpose. There is a long history of earthen building here in the Southwest. For example, Taos Pueblo buildings are one of the oldest continuously inhabited structures in Turtle Island. In the pueblo, many indigenous women would construct and plaster the cob/adobe walls. Later on, the enjaradoras, adoberas and others would partake in building & maintaining homes with mud across the region.

This spring & summer, I started to meet & assist a few women who have or were building their own homes in Taos, including Jana Greiner & Alice Ko. I then volunteered with an organization called Cornerstones (with Angela Francis & Issac Logsdon) in an excavation process of a 250 ish year old adobe structure in Chimayo, NM, which melted, returning back to the land. We reused the melted mud to reconstruct adobe bricks that will be used to rebuild the walls. I worked a few shifts in an adobe yard - New Mexico Earth Adobe in Albuquerque with Helen Levine. Helen had mentioned to me the work of Joanna Keane Lopez, who would soon hold a workshop where a group of us assisted her in building an adobe sculptural piece for a gallery exhibition. I had illuminating & generous conversations with Ryan Flahive and Dr. Theodore Jojola about adobe, archives, and indigenous architecture. During my own housing search, I met many builders including an elder from Nambé Pueblo whose family had built several adobe structures. I visited from a distance Dar Al Islam, an adobe mosque and education center in Abiquiu, New Mexico designed by Egyptian architect Hassan Fathy. His work brought together Egyptian builders and New Mexico locals to build and exchange knowledge especially on adobe vault and dome techniques 10.

My re-introduction to architecture beyond the colonial industry was through these meaningful conversations & work sessions. The different vantage points I experienced from working with adobe & natural materials, learning its (oftentimes complicated) histories, and repeatedly being led to these rich exchanges, solidified an important understanding. It is vital to engage in building rooted in earth based skills that foster home & nourishment from the physical level to the spiritual and emotional, on multiple planes of existence: the scales of self, community, land and cosmology. I began to answer old curiosities: what does it mean to recreate what we knew of home & the elusive “community”, when so many of us have been strategically shuffled around? when in some cases (and if even possible) returning to our “homelands” would actually be harmful or extractive? How do we reclaim heritage beyond any form of supremacy? I found a path through the earth, and the good work of untangling all our distorted relationships to ourselves, the earth and each other. Adobe deeply (and widely) connects desert people across the world.

I must mention as a designer, architect & builder I had studied & worked in Eurocentric, colonial and male led academic & professional spaces. Accompanying me in these spaces was a sense of grief at the erasure of the myriad of wisdoms I hoped to be in community with. Because the erasure was & is so severe in those spaces, much of my efforts to remember and reclaim other ways of being, doing, thinking, and cultivating home, community, architecture and building, was led by a felt sensation, distant memory & inner knowing, rather than mental or external validation. My persistence has thankfully led me to more recently meet and learn from the people & places I am meant to. Along with everyone previously mentioned, one such person is Rina Swentzell.

RINA SWENTZELL

In contrast to most university architecture schools, the primary objective of the IAIA architecture program would be to promote architecture as a human expression which helps reveal the interrelationships of life

—Rina Swentzell

This quote is from a 1982 letter proposing an architecture program for the Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA), describing philosophy & courses 11.

My first introduction to Rina Swentzell was through learning about her daughter Roxanne Swentzell, who is also an adobe builder, seed keeper, sculptor and founder of Flowering Tree Permaculture Institute. Among many roles, Rina Swentzell was an architect, builder, mother and community advocate from Kha’po Owingeh otherwise known as Santa Clara Pueblo where she grew up in the 1940s. Rina Swentzell is an ancestor and matriarch in this work. One of the prominent aspects of Swentzell’s work is the amount of loving labor put into explaining her Pueblo world view, the way it informs architecture, and how it contrasts with imposed Western-European views.

As I shuffled through paper drafts and articles of hers housed at the New Mexico History Museum Library, I couldn’t help but feel a sense of relief and resonance. Over the past months, I have been experiencing more of what Rina left behind through archives of recorded public conversations, interviews and many of her written pieces. In the following paragraphs, I will attempt to share some recurring themes in her work. I hope that this humble introduction to her work will encourage others to learn from her wisdom, as well as to support & learn from those in their community who hold deeply rooted memories & knowledge of place. I will then describe how these & similar themes have influenced my consciousness about the relational architecture of earthen buildings.

As the quote above illustrates: architecture, like art, like any endeavor, is a form of human expression that speaks to meeting needs, nurturing life, and relationships 12. They can not be siloed into separate “disciplines”. All efforts are expressions of the sacred, cosmology, and the environment & context from which they spring forth. Thus architectural form, values, lifestyle, culture and world view are all aligned 13.

In this way, Rina illustrates unity. She describes how duality creates the dynamism of life, as well as the need to balance the many forces in life & nature. We come from ancient waters and earth. With the balancing & mixing of clay, water & other materials, we mold vessels for nourishment and living through pottery & adobe homes. In return, they mold us. Adobe homes are flexible and adaptable, expressing variety in oneness of material & intention. The future and past collapse in the present. Rina says, we must walk, move and talk with care, because we affect the world with our actions & responses on every scale 14.

God exists to be shaped

God is Power—

Infinite,

Irresistible,

Inexorable,

Indifferent.

And yet, God is Pliable—

Trickster,

Teacher,

Chaos,

Clay.

God exists to be shaped.

God is Change.

—Octavia Butler, The Book of The Living.

Swentzell speaks of the po-wa-ha “water-wind-breath” - the essential non-discriminate life force that flows through all 15. The breath exists in the animate and inanimate, including the adobe structures which also have a life cycle. Adobes return to the earth once they die, reuniting with their origins. The spiraling, cyclic nature of time is embodied in this dynamic. Although bodies and structures alike are impermanent, they always belong & return to the original continual breath, reuniting & transforming back to their elemental essence. This understanding of time is marked by events and ceremonies rather than linear numbers or a sort of accumulation. Across the globe many native communities hold rituals & blessings for both the process of building and maintaining homes16.

These are some values that ensured cultural continuity & adaptation. When these values and community self-determination are interrupted, acculturation occurs, which is a threat to all of our survival if we are to uphold pluriversality as a strength. In the assimilating pressures of European colonial culture, Swentzell points to how the notion of the individual is placed above the whole or communal. For example the design of one home was placed above the design of the community or town plan. For Rina, this was exemplified in the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) day schools and US Department of Housing & Urban Development (HUD) housing designs in Santa Clara Pueblo. Federal standards went against traditional planning & methods such as building with mud & adobe, marking a departure from earth in many ways, both in construction and in symbolism. Separation manifested in distance and arrangement of structures. Fencing and borders instilled a sense of distrust and policing. The monumentality, clinicalness & hearierchy in form and programming of spaces, were described as sad and dulling the curiosity & confidence of those interacting with them. The relationship/interaction(touch/taste/smell) of buildings was prohibited 16.

Ways of being clash in the contrast of absolute truths versus relative truths & stories which evolve and change depending on the story teller, the listeners, and the context of sharing. Rina often brings our attention to the importance of different vantage points, & how they offer more expansive views, giving us multiple true perspectives of the whole that is relational & contextual. She grounds us in an example of how this contrast of “truths” plays out in architecture and the legal world of building codes. Building codes act as absolute external standards, universal truths and conditions with little room for contextual adaptations. They repeatedly fail to address local concerns. The cost of such “safety measures” and assumptions on the universal “right” way, and the resulting absence of contextual, environmental and human participation is ultimately a diminished quality of life 13.

Another clash is rational vs. intuitive right to participation. Rational participation takes on form in the professionalization, specialization & alienation of building, designing and architecture. Traditionally, in the Owingeh there were unself-conscious, intuitive, informal, inclusive and empowering ways for everyone to participate in building. Rina said “Learning happened easily. It was about living. In fact, the word for learning in Tewa is haa-pu-weh, which translates as “to have breath” To breathe or to be alive is to learn 11. Rina summarized simply that building with the community meant “the most direct method is combined with the most accessible materials” 16.

SCALES & CIRCLES OF RELATIONAL INFRASTRUCTURE

In the next paragraphs, I will describe seven scales or circles of relationships that working with adobe has given me a deeper understanding of. Swentzell said architecture is a “human expression which helps reveal the interrelationships of life” 6. Relatedly, adobe is an embodiment and conduit of relational infrastructure.

1. My relationship to self and purpose.

I hope that by sharing some of my background, as well as the places & people I’ve learned with and from, gives you a sense of my lens, responsibilities, gifts & challenges, which are all woven together. I hope that it explains a bit of how I was led to this work, why it is important & purposeful for me, and my relationship to the research themes presented here of earthen building, home, belonging and social environmental healing.

2. The relationship of the materials adobe consists of, and the elemental relationships in the process of adobe making.

Adobe consists of water, clay, sand (or another type of aggregate), and straw (or another type of fiber). Each material has a specific property. They tell us how to interact with them and how they will interact with each other. There is also the relationship between elements of earth (clay+sand+fiber), water, fire (sun), wind (climate dryness or moisture). Taking into account the alchemy that happens between materials and environmental conditions, adobe mixing isn’t a formulaic process but one that relies on observing and feeling into how each part, condition & process are relating & affecting another.

3. The relationship of builder to soil, land and respectful harvesting.

The global history of building with mud & adobe is dependent on relating with the land & elements, knowing where to harvest suitable clay, and doing so in a respectful & reciprocal way. In Rina Swentzell’s book “Children of Clay”, she described a process of honorable harvest, which involved speaking to Clay Old Woman, asking permission, offering gratitude, and stating intentions17. I was personally taught to leave an offering and never take more than needed. In essence, this care work is a part of land stewardship, which allows the perpetuation of lifeways.

4. The relationships formed with people & community that have enabled, encouraged, and deepened my consciousness & understanding of earthen building.

As mentioned earlier, the most relevant knowledge exists within relationships and not archives. There are so many people, meaningful experiences and generous conversations that were shared with me, that have deepened my consciousness and widened my understanding of myself, of others and of what it means to work & build with the earth.

5. The relationship of the many hands & labor this work asks for.

The work of building an adobe structure or home, as well as its maintenance is work that requires community. The physical nature of moving, mixing and shaping earth is one that is demanding, yet joyful and natural when done communally. If we are to understand labor through a social and environmental justice lens, we will observe that labor is always happening. However, in capitalist structures, labor is divided into valued vs. unvalued. The latter is typically invisibilized, gendered, classed, racialized, or not always public - such as spiritual, domestic & emotional labor. Much of the adobe work done by both indigenous and migrant women in the Southwest is not uplifted outside the region.

6. The relationships of building and maintaining physical vessels for living & nourishing the body, home & community.

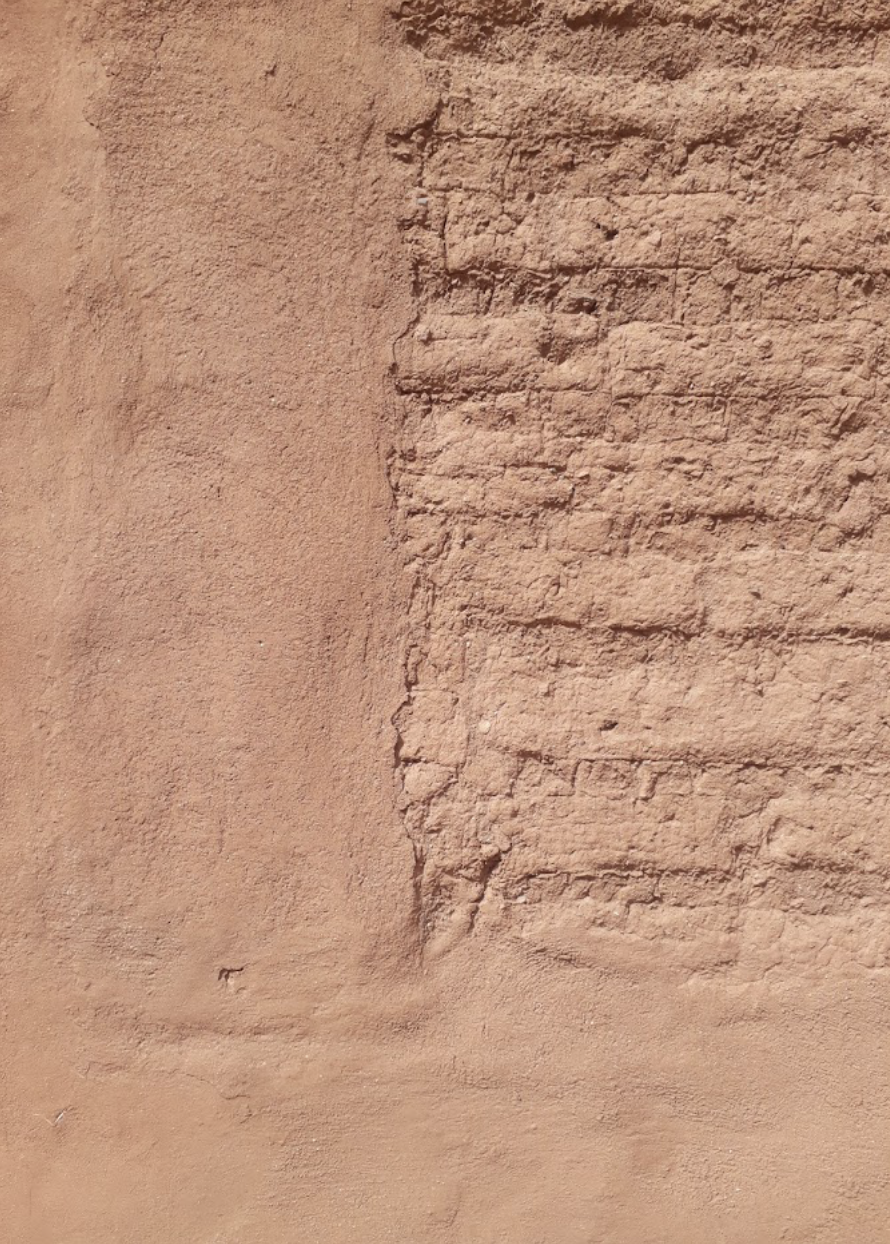

Retrofitted adobe home originally built in the early 1900s in Llano, NM. Courtesy of author.

This work at its core is cyclic & ritualistic. All our vessels are in deep relationship with the sun & moon. The simple necessary act of seasonal adobe replastering & maintenance can be very healing.

All that you touch you Change.

All that you Change Changes you.

The only lasting truth is Change. God Is Change.

—Octavia Butler, The Book of The Living

Photos at the late Felipe Ortega’s pottery studio in La Madera, NM 2020. Courtesy of author.

This is an active living form of reciprocity: what we build, builds us. What we care for, cares for us. What we maintain, maintains us.

7. The relationship with what is bigger than us, the creative force, cosmos, time & space, and the cycles of life, death and transformation.

Working with the earth is simultaneously grounding and uplifting. When I place my hands in the soil to plant seeds, watch them grow, when I mix clay, and mold it to make or repair a vessel, I feel direct contact with & nourishment of these essential relationships. There is mystery, magic and miracle in earth work. I feel a connection to ancestors: human, plant, elemental and beyond. I feel contact with descendants praying me into this commitment, this sacred work for all our continuation.

WHAT DISRUPTS THE MAINTENANCE OF RELATIONAL INFRASTRUCTURE

Even after my initiation and thirty years of experience, I’m still learning the how and the why of what I call “indigenous technologies.” We forget that thousands of years ago people were in touch with a different kind of technology — non-Cartesian, non-Newtonian technologies that could get us from point A to point B without environmental side effects. Somehow we are not imaginative enough in the West to consider the possibility of a parallel technological pathway that does not cause illness, pollution, or the extinction of species.

— Malidoma Somé, Between Two Worlds

The many facets of connection, and the necessary continual acts of relational maintenance, balance & healing are under constant challenge. We face many ruptures due to the barriers placed between us and our right to practice ancestral liberatory technologies.

Colonial technologies divide. As I write this in English, I must mention how language is used to fragment. In my studies, adobe & earthen buildings are typically categorized as “vernacular” or “traditional” architecture, separate from “contemporary” architecture. Yet earth is currently the most widely used building material as Ronald Rael says. An estimate of between one third to one half of the world’s population (about 3 billion people) live in earthen residential buildings, not including places of work & worship 18. Folded into these categorizations are the undertones of class discrimination and a relegation of indigenous technologies to a distant past.

At the same time, the appropriation, aesthetic mimicking & gentrification of indigenous technologies are ubiquitous. The popularity of associated “styles” for rich architectural clients has made it difficult for genuine practices to perpetuate. These challenges alongside co-opting definitions to serve marketing ends, such as overuse of the word “sustainable”, has convoluted the meaning of words and their material implications. Within ancestral land based technologies, integrated “sustainability” happens because of the embodied ethos of reciprocity & relationality. “Sustainability” is not a separate agenda, but embedded in what is made and within the process of making itself. These linguistic tools are a reflection of economic class struggles, hierarchies, & other capitalist issues, which fall under colonial technologies that occupy our space, time, memory & spirit.

The colonization of space looks like stolen lands, strategic severing from land based practices, forced displacement, fragmentation of families and lifeways, and a commitment to land depletion as justification for “innovative” & “modern” life. Kathryn Yusoff frames this spatial violence through geology itself - “As the Anthropocene proclaims the language of species life—anthropos—through a universalist geologic commons, it neatly erases histories of racism that were incubated through the regulatory structure of geologic relations. The racial categorization of Blackness shares its natality with mining the New World, as does the material impetus for colonialism in the first instance. This means that the idea of Blackness and the displacement and eradication of indigenous peoples get caught and defined in the ontological wake of geology. The human and its subcategory, the inhuman, are historically relational to a discourse of settler-colonial rights and the material practices of extraction, which is to say that the categorization of matter is a spatial execution, of place, land, and person cut from relation through geographic displacement (and relocation through forced settlement and transatlantic slavery). That is, racialization belongs to a material categorization of the division of matter (corporeal and mineralogical) into active and inert. Extractable matter must be both passive (awaiting extraction and possessing of properties) and able to be activated through the mastery of white men. ” 19

The colonization of time looks like placing monetary value on time in exchange for survival. It is dislocating time & labor from their natural cyclic and ceremonial nature. It is prohibiting people & communities from exercising self determination & self sustenance, through mandatory capitalist participation in wage labor. The colonization of time is limiting & prohibiting communities from exercising their rights to take as much time for grieving, healing, rituals and mutual aid.

The colonization of memory looks like forced assimilation, and a culture of historic amnesia. It is the erasure of existing cultures, or the flattening of them. The colonization of memory is the denial of historic trauma and perpetuating current trauma. It is the siloing of knowledge into colonial taxonomies.

Compounding oppressions have led to the disruption of extended relations. Links are broken in the passing of generational knowledge. Bearers of knowledge are aging and are unsupported financially or morally. Aspiring multigenerational & pluricultural learning spaces become unsafe due to untended lateral violence, trauma and other factors. Harmful coping mechanisms, addiction and incarceration further separate communities. This is what I understand to be the mining of the human spirit as described by John Trudell. The confluence of these forces has led to the physical and metaphysical occupation of our attention, energies and spirits.

This is not a renunciation of all western and modern technologies. Many were created in efforts to provide more safety, control & comfort. This is a question of how to intentionally reconfigure and remix the knowledge & technologies we have, both ancient & modern. How do we metabolize grief and trauma towards a remembrance of our power, sovereignty and healing ways? How do we truly relate to place, and develop climate resiliency - as storms, droughts and wildfires increase? And yet still, how do we craft joy & play within the mix of all of this?

I believe the revival & contextual adaptation of adobe, earthen and woven architectural practices to be a step towards answering some of these questions. I believe this to be one way oppressed peoples can reclaim ancestral technologies, materially & relationally, and move towards housing sovereignty & total sovereignty.

REPAIRING & REINVIGORATING CULTURES OF BELONGING

Another way we could describe relational fragmentation is the enactment of borders (in every sense of the word). Operationalizing borders through extractive social and material relations has created the very dangerous & violent conditions that require the crossing of borders, and the necessity of their abolition. As the number of refugees increases due to wars and climate chaos, kinship across all types of borders is increasingly necessary for our collective survival, one that is responsive to the specificities of where migrants are coming from and where they go. To be diasporic & in place asks for a new kind of kinship: land & interspecies kinship beyond ownership, nationhood & assigned nuclear family.

So how do we revive cultures of true belonging? What could kinship become amidst the dance between modern & ancestral technologies?

In the following paragraphs I will share dreams & visions for a remembrance of ancestral liberatory technologies, cultures of belonging, as well as grounded examples of related efforts.

VISION:

Remembrance, return, rematriation, and reparations.

GROUNDING:

Neema Githere writes about the need to decolonize to re-indigenize: education, nutrition, technology, and spirituality. They describe a two-fold process:

“1. The abandonment of ideals and systems established through colonization. 2. An evolution towards- and rememory of: ancient modes of knowledge and community” 20

A few current practices related to rematriation and reparations in North America include Sogorea Te’ Land Trust and Soul Fire Farm’s Reparations Map.

VISION:

Generational & sustained belonging.

Tending an unshakable sense of belonging within self and community.

Connecting & reconnecting between all circles & scales of relations.

GROUNDING:

Creating multi generational education programs for earth based, place based & outdoor programs, as well as body & heart literacy programs.

Some examples related specifically to adobe/earthen building skills are:

Pueblo youth adobe summer program 21. And Camp Adobe 101 22.

VISION:

Locating ourselves in liberating relationships. Uplifting the medicine of revolutionary Black, diasporic, indigenous & queer consciousness & love.

GROUNDING:

It is important to locate ourselves in the context of liberation movements. Locating ourselves in time and space of freedom efforts gives us purposeful perspective, asking ourselves: are we working within the status quo? Challenging the status quo to reform? Working on abolition? Or working to create outside of current systems when possible? Where is our agency? Damian Alan Pargas describes an example of the distinctions of “the spaces of Black freedom between the revolutionary era and the U.S. Civil War. Alan speaks of formal freedom, regions in which slavery was abolished and refugees were legally free; sites of semiformal freedom, areas in which abolition laws conflicted with federal fugitive slave laws; and sites of informal freedom, places within the slaveholding South where runaways formed maroon communities or attempted to blend in with free black populations” 23.

What time is it on the clock of the world? Grace Lee Boggs asked . “American revolutionary and philosopher Grace Lee Boggs along with her husband and civil rights activist Jimmy Boggs visualized 3,000 years of human history on a 12 hour clock where every minute represents 50 years. Extending this metaphor, they argued that revolution as the primary driver of social change is only 5 minutes old. Grace lived to be 100 years old, and worked with thousands of young organizers; asking them to engage with this model of time and “re-imagine spaces and institutions in which healthy relationships with people, nature, and ourselves can be built - by creating beloved communities.”” 24

Queer love especially has created chosen kin outside the confines of, and often due to exclusion from, the nuclear family. I remember Treva Carrie Ellison saying at a lecture: “demilitarize kinship & the home” describing how the sanctification of the nuclear family unit happened during the world war II era as a campaign to bypass accountability for the fragmentation war, abuse, poverty...etc caused. The nuclear family as the only legitimized form of kinship, drew the borders between who and who is not deserving of care, which conveniently required more consumption, reviving the post war economy 25.

VISION:

Reviving material cultures, memories, meanings, & values.

GROUNDING:

We must reclaim, & revive material cultures as portals of memory, ceremony, & transformation, instead of deadened objects to be sold & consumed. We must question why adobe is often labeled as “labor intensive”, when mass manufactured materials inherent & embody a complex web of exploited labor and extraction. Materials, natural and manufactured, hold the labor and energies of all its parts & processes. Forgetting this fact has led to the objectification and whitewashing of our material world. Adobe comes from the Arabic word at.-t.ūb الطوب meaning brick. Although mud has intuitively been used all around the world, some building technologies traveled to New Mexico from Africa & South West Asia by way of Spanish colonization. Waves of colonization, faith and migration linked indigenous, settler, migrant & stolen communities. These relations reverberate throughout time and space in unexpected ways, ultimately leading to adaptations, resiliency strategies, exchange and remixing of technologies. We must move beyond romanticizing the false notion of a “great melting pot” towards reckoning with the truth of our inheritances, where we go from here, and to more deeply understand relational dynamics that shape our material cultures & resilience. In this way, the material is closely shaped by immaterial. Other examples of material resilience & resistance include: Pueblo Revolt knotted cord, silver protection amulets of West Asia, and Underground Railroad quilts.

VISION:

Remembering the technologies of ritual & ceremony, which strengthen relational infrastructure & maintenance.

GROUNDING:

A ritual is a ceremony in which we call in spirit to be the driving force, the overseer of our activities. It is a way for us to find our way to wholeness, peace, self-acceptance, and acceptance of others. Ritual allows us to connect with the self, the community, and the natural forces around us. Ritual helps us remove blocks between us and our true spirit.

—Sobunfo Somé

We must liberate time/space/labor/memory from capitalist and colonial clutches, back into earth time, back into possibility & magic, back into awareness & devotion to cyclic renewal. Ritual allows us to expand into more choices, and to access different spaces and timelines. It liberates us from weaponized “rationality” & binaries, and bridges the distance between us.

A few examples of community affirming rituals which adobe & earthen building have evoked:

Dabke

Dabke is a dance native to South West Asia and the current Arab world (popular in Palestine, Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, and Yemen). Dabke is a celebratory dance (often performed in marriage ceremonies) which combines circle and line dancing, and foot stomping. Recently it has been practiced at protests as well. Folk tales point to adobe construction & repair being the origin of this dance, as community members would come together to stomp on the mud mixture to repair their homes & adobe roofs. It was said that in the winter, people would link arms and sing to keep warm while mixing the mud plaster 26.

Cyclic replastering of Great Mosque of Djenné.

Every year in a spring festival, the community of Djenné, Mali come together to maintain their mosque. Replastering the multi story structure brings all generations of the community together. Maintenance considerations are embodied not only in this communal act, and celebration, but also in the built-in scaffolding of the mosque’s design27.

Replastering of the Grand Mosque in Djenné, Mali.

Photo by Paul de Roos. (fig.4)

VISION:

Integrated liberation. Integrated systems.

Home sovereignty is intimately linked with housing, land, body, food, water & cultural sovereignty. Home sovereignty is about maintaining the web of life affirming systems28 - a type of care economy.

GROUNDING:

Home sovereignty goes beyond housing sovereignty, beyond the narrow “field of architecture” , towards the expansiveness of belonging & home, and how that manifests on a material plane. Changing material conditions is a profound form of justice that heals.

We must all join in on the work of making these critical connections from our unique & needed access points. Decriminalize caretaking. Drop the charges of water and land protectors. Uplift the work of matriarchs, women, femmes, non binary and trans people who build and maintain both in domestic settings and beyond. Other efforts to be inspired by & support include:

Tewa Women United: soil mycoremediation.

New Mexico Acequia Association: collective water stewardship.

Art.coop: Solidarity economy and creative cooperatives (i.e. East Bay Permanent Real Estate Cooperative).

Movement Generation: strategies for just transitions to regenerative economies.

Soul Fire Farm: BIPOC food and medicine sovereignty.

Resmaa Menakem, Meenadchi, Accountability Mapping with Daria, &

Generative Somatics: embodied liberation through somatic & nervous system rewiring, and conflict navigation skills.

VISION:

Adobe & abolition.

Related to the previous vision of integrated liberatory systems, I feel the need to bring attention to prison & police abolition. Ruth Wilson Gilmore says “abolition is about presence, not absence. It’s about building life-affirming institutions.”28 And thus it isn’t a stretch to emphasize how perpetuating indigenous technologies is a path towards abolition (adobe & earthen building as just one iteration).

GROUNDING:

To ground us in the connections between abolition, infrastructure, climate resilience, indigenous technologies and international liberation coalitions, here is more of Ruth Wilson Gilmore’s wisdom:

“In the United States, where organized abandonment has happened throughout the country, in urban and rural contexts, for more than 40 years, we see that as people have lost the ability to keep their individual selves, their households, and their communities together with adequate income, clean water, reasonable air, reliable shelter, and transportation and communication infrastructure, as those things have gone away, what’s risen up in the crevices of this cracked foundation of security has been policing and prison. Now it’s not that surprising when we stop and think that if in an organized way, state and capital abandon people, something is going to arise to shape and direct what those people do who are not absorbed back into the political economy in other ways. It’s really not that surprising, though it is frightening”. 29

“Abolition has to be “green.” It has to take seriously the problem of environmental harm, environmental racism, and environmental degradation. To be “green” it has to be “red.” It has to figure out ways to generalize the resources needed for well-being for the most vulnerable people in our community, which then will extend to all people. And to do that, to be “green” and “red,” it has to be international. It has to stretch across borders so that we can consolidate our strength, our experience, and our vision for a better world”. 29

VISION:

Home sovereignty.

Home sovereignty is having an abundance of choices, and the right to self determination in answering the: what, where, who, how and why of home & belonging. Sovereignty not as “rugged individualistic” survival, but as mutual liberation & thriving. When it comes to housing: everyone would be housed. Housing would be a human and cultural right. We would have choices with building types, processes, rituals & materials.

GROUNDING:

When thinking specifically of housing sovereignty, I am reminded of what Porter Swentzell said, that home is our inheritance and our birthright 30. Only a few generations ago, many of our ancestors knew and were able to build their own homes. I am reckoning with how just two generations ago, both my parents’ families were living close to the land & farming. I refuse to relinquish that knowledge. Many of us come from ancestors who did what they must to survive, survive the truth of displacement, and survive the truth of living in colonial spaces & temporality.

And now many of us live in a time and place where access to land, material, building knowledge & support are made difficult or impossible. To remake home & housing sovereignty a reality, we must cultivate relevant knowledge, values, responsibilities & policies. One way would be to make accessible the study & practice of earthen building. Another would be to challenge current institutionalized structures like building codes that make the use of earthen materials illegal. For example, Sasha Rabin & her team have recently taken the initiative to perform fire tests on cob walls to address some of these legal limitations 31.

Every generation confronts the task of choosing its past. Inheritances are chosen as much as they are passed on. The past depends less on “what happened then” than on the desires and discontents of the present. Strivings and failures shape the stories we tell. What we recall has as much to do with the terrible things we hope to avoid as with the good life for which we yearn. But when does one decide to stop looking to the past and instead conceive of a new order? When is it time to dream of another country or to embrace other strangers as allies or to make an opening, an overture, where there is none? When is it clear that the old life is over, a new one has begun, and there is no looking back? From the holding cell was it possible to see beyond the end of the world and to imagine living and breathing again?

—Saidiya Hartman, Lose Your Mother: A Journey Along The Atlantic Slave Route

Finally, my work here has focused on adobe, belonging & liberation as well as the process of reflecting & contextualizing. This process is inseparable from my understanding of material/immaterial cultures, realities, and of growth. So I leave you with the following questions that may assist you in locating yourself in time/power/place no matter which field you work in:

PLACE

What would it look like to honor land & indigenous lifeways in your town?

How do you access your freedom where you are?

Are there spaces in your community that already embody a sort of freedom to you?

What would it mean to memorialize struggles for liberation?

What are alternate ways than (insert racist/tokenizing/oppressive regional festival) of celebrating and re-visioning place?

What would a decolonized/indigenized community look and feel like to you (dream big & brave!)? What would the initial steps be towards achieving such a community?

PAST

What stories, beliefs, culture, ways, language and ceremony did you inherit, and from whom?

What are the generational gifts you’ve inherited?

What are the generational responsibilities you’ve inherited?

What are the stories that have been erased or overlooked?

FUTURE

How can we be in conflict in a generative way?

How do we embody healthy accountability?

How do we honor diversity and not perform it?

How do we create new ways of belonging not predicated on exclusion?

What does intersectional generational: ancestral & descendant healing look like at this present moment?

PRESENT

What are the small everyday acts that help build intimacy & strengthen relationships with self and others beyond crisis response?

Can you think of “invisible norms” and how they hinder our belonging and our liberation?

What values are you committed to?

What practices/rituals/ceremonies assist you in recommitting to the values you’re calling into this world?

REFERENCES

Rowen White, “Seeds, Grief, and Memory”, Finding Our Way Podcast hosted by Prentis Hemphill, May 24th 2021, www.findingourwaypodcast.com/individual-episodes/s2e6

Shawn Wilson. “Research Is Ceremony: Indigenous Research Methods”, Fernwood Publishing 2008.

Tonia Sing Chi, “Building Reciprocity: A Grounded Theory of Participation in Native American Housing and the Perpetuation of Earthen Architectural Traditions”, Tonia Sing’s website, 2018, www.toniasing.com/building-reciprocity

Nááts’íilid Initiative, ”About”, https://www.naatsiilid.org/

Donna Horowitz, “Indian Burials at State Missions go Unmarked”, SFGATE, June 19th 1995, https://www.sfgate.com/news/article/Indian-burials-at-state-missions-go-unmarked-3144002.php

Caitlin Harrington, “The Lesser Told Story of The California Missions”, hoodline, March 20th 2016, https://hoodline.com/2016/03/the-lesser-told-story-of-the-california-missions/

Santa Barbara Trust for Historic Preservation, “Our History”, www.sbthp.org/ourhistory

Giana Magnoli, “Preservation, Respect for Past Remain Key Elements of Santa Barbara’s Vision for Its Future“, NOOZHAWK, October 17th 2017, https://www.noozhawk.com/article/reimagine_santa_barbara_past_preservation_future_20171017

Tizziana Baldenebro, “The Trial of California’s Missions”, The Avery Review 41, September 2019, www.averyreview.com/issues/41/trial-of-californias-missions

Fatima van Hattum, “part6 MUD”, Tilt Podcast: Unsettled Series, www.podbean.com/ew/pb-hhc78-fa19e1

Rina Swentzell, “1982 Architecture program proposal for the Institute of American Indian Arts, philosophy & courses”, Jeremiah Iowa Architectural Collection (AC358), Fray Angélico Chávez History Library/New Mexico History Museum, Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Rina Swentzell, “Walk Carefully in The World: Mimbres and the Pueblo Tradition”, Studio Potter Vol 28 Issue 1, 1999.

Rina Swentzell, “Pueblo Culture & Built Form”, Jeremiah Iowa Architectural Collection (AC358), Fray Angélico Chávez History Library/New Mexico History Museum, Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Rina Swentzell & William N. Morgan, “Ancient Architecture of The Southwest”, University of Texas Press 2013.

Rina Swentzell, “An Understated Sacredness”, MASS: Journal of the School of Architecture and Planning, University of New Mexico 3 (Fall) 1985.

Rina Swentzell, “Conflicting Landscape Values: The Santa Clara Pueblo & Day School”, Places 7(1), 1990.

Rina Swentzell, “Children of Clay: A Family of Pueblo Potters”, Lerner Publications Company 1992.

Ronald Rael, “Earth Architecture”, Princeton Architectural Press 2009.

Kathryn Yusoff, “A Billion Black Anthropocenes or None”, University of Minnesota Press 2018.

Neema Githere, “Reindigenization”, Neema Githere’s Are.ne channel, www.are.na/neema-xx/reindigenization

New Mexico Department of Cultural Affairs, “Pueblo Students Learn Architecture through Summer Reading Program & UNM School of Architecture Partnership”, DCA website, August 1st 2017, http://media.newmexicoculture.org/press_releases.php?action=detail&releaseID=585

The Awesome Foundation, “Camp Adobe 101”, May 2015, www.awesomefoundation.org/en/projects/47541-camp-adobe-101

Damian Alan Pargas, “Fugitive Slaves and Spaces of Freedom in North America”, University Press of Florida 2020.

Grace Lee Boggs, What Time Is It? Archive website, www.whattimeisitarchive.com/

Treva Carrie Ellison, “Under Construction” University of Maryland Lecture, September 16th 2020, https://arch.umd.edu/events/under-construction-lecture-treva-ellison

“The Dabke-An Arabic Folk Dance”, History and Development of Dance website, May 9th 2013, https://dancehistorydevelopment.wordpress.com/2013/05/09/the-dabke-an-arabic-folk-dance/

Dr. Elisa Dainese, “Great Mosque of Djenné”, Khan Academy website, https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/ap-art-history/africa-apah/west-africa-apah/a/great-mosque-of-djenne

Ruth Wilson Gilmore, “What are we talking about when we talk about “a police-free future?”, MPD150 website, https://www.mpd150.com/what-are-we-talking-about-when-we-talk-about-a-police-free-future/

Ruth Wilson Gilmore, “Ruth Wilson Gilmore Makes the Case for Abolition (Part 1)”, The Intercept Podcast, June 10th 2020, https://theintercept.com/2020/06/10/ruth-wilson-gilmore-makes-the-case-for-abolition/

Dr. Porter Swentzell and Garron Yepa, “Harvard Indigenous Design Collective, Mixing Mud Lecture”, December 16th 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zKbVTPioD40

Doug Johnson, “It’s Time to Rethink the Cob House”, Discover Magazine, July 30th 2021, https://www.discovermagazine.com/technology/its-time-to-rethink-the-cob-house

IMAGES

Figure 1. Originally published on: https://worldarchitecture.org/architecture-projects/fhmn/kuwait-vernacular-architecture-project-pages.html

Figure 2. Originally published on: www.santafenewmexican.com/life/home/we-plaster-our-walls-valuing-a-heritage-technology/article_47154519-b16b-55a6-8c52-0b5f52174d00.html

Figure 3. Originally published on: http://newmexico.imagepast.com/collections/enjaradoras-chamisal-1940

Figure 4. Originally published on: https://www.bbc.com/travel/article/20190801-the-massive-mosque-built-once-a-year

NON COMPREHENSIVE RESOURCE LIST

Practices

Earth USA conference https://www.earthusa.org/

Terra: World Congress on Earthen Architectural Heritage https://www.terra2022.org/

Cornerstones Community Partnerships

https://www.cstones.org

Adobe in Action https://www.adobeinaction.org

The Earth Builders Guild https://theearthbuildersguild.com

Cob Research Institute https://www.cobcode.org/mission

Tierra Firme http://tierrafirmeprojects.com/

Flowering Tree permaculture https://www.floweringtreepermaculture.org/

Canelo Project https://caneloproject.com/

Sogorea Te’ Land Trust www.sogoreate-landtrust.org/2021/11/30/queer-projects-on-indigenous-land/

People

Rina Swentzell

Roxanne Swentzell

Athena Steen

Helen Levine

Carol Crews

Anita Rodriguez

Joanna Keane Lopez

Ronald Rael

Hassan Fathy

Nadir Khalili

Buildings

Taos Pueblo (Taos, New Mexico)

Yakhchāl, Iran

Arg-e bam, Iran

Ziggurat of Ur, Iraq

Walled City of Shibam, Yemen

Musgum Homes, Cameroon

Great Mosque of Djenné, Mali

Aït Benhaddou, Morocco

Books (non technical)

Dwellings: the House Across the World by Paul Oliver

Mud, Space and Spirit by Alan Macrae & Virginia Gray

Earth Architecture by Ronald Rael

Early Architecture in New Mexico by Bainbridge Bunting

Racing Alone by Nadir Khalili

A Billion Black Anthropocenes or None by Kathryn Yusoff

Belonging: a Culture of Place by bell hooks

Podcasts, Videos & Lectures

Rina Swentzell: An Understated Sacredness Video

https://www.newmexicopbs.org/productions/colores/rina-swentzell-an-understated-sacredness/

Stuccoed in Time Podcast

https://99percentinvisible.org/episode/stuccoed-in-time/

Reports & Articles

Transforming building regulatory systems to address climate change report by David Eisenberg

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09613218.2016.1126943

Earth Architecture - Valorization & Underestimation by Norma Barbacci

https://www.normabarbaccipreservation.com/new-blog/2020/4/22/earthen-architecturevalorization-and-underestimation-lecture

Ephemeral Narratives: Design Considerations for a Future Past by Brandon Ortiz

https://averyreview.com/issues/52/ephemeral-narratives

Earth Architecture curated website

https://eartharchitecture.org/

My Mother, The Builder by Rose B. Simpson

https://www.newmexicomagazine.org/blog/post/my-mother-the-builder-rose-simpson-

roxanne-swentzell/

Lead with Listening: A Guidebook for Community Conversations on Climate Migration

https://www.climigration.org/guidebook

PUEBLO Analysis: An Indigenous Planning Tool for Ysleta del Sur Pueblo by Theodore (Ted) Jojola & Saray Argumedo

https://archleague.org/article/ysleta-del-sur-pueblo/

Reclaiming the Land Part 3: A conversation with the founders of Shelterwood Collective by Amanda E. Machado

https://www.theoutbound.com/amanda-e-machado/reclaiming-the-land-part-3-a-conversation-with-the-founders-of-shelterwood-collective

Exhibits

Mujeres Nourishing Fronterizx Bodies: Resistance in the Time of COVID-19, MOCA Tucson Exhibit

https://moca-tucson.org/exhibition/mujeres-nourishing-fronterizx/

were-:Nenetech Forms, MOCA Tucson Exhibit

https://moca-tucson.org/exhibition/were-nenetech-forms/